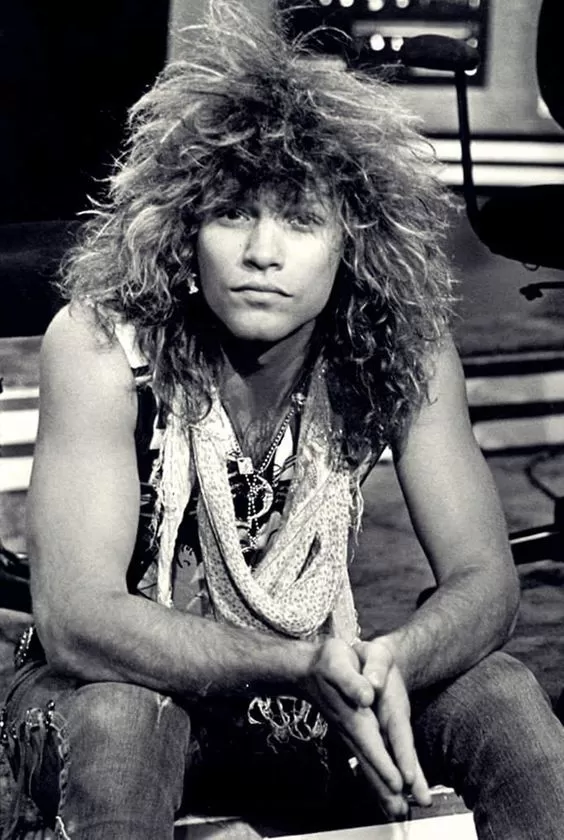

When I was ten, I took a picture of Jon Bon Jovi to my hairstylist and said, “I want to look like this.”

Three hours and one spiral perm later, I was vibing more Shirley Temple than J.B.J. I cried almost as hard as the Great Cabbage Patch sell out of Christmas 1983.

There were the swim lessons where I got leeches.

There were the 5th grade mean girls.

There was the culture shock move from suburban New York to rural Maine and my parent’s divorce which included six moves and three schools in one year. There was the Type I diabetes diagnosis at age 17 and the cross country move for college.

And many, many others.

Resiliency. We know it’s a good thing, something worth instilling in our kids.

Sure. Though maybe not right now. Maybe when they’re a little older, a little stronger.

Challenge used to be hard wired into life, an unavoidable and standard part of growing up. Dealing with that stern 4th grade teacher, a dinner served that you didn’t like, fundraising (by yourself, not your parents putting it on Facebook), not getting a trophy, being bored, doing chores.

(Getting picked last for P.E. class. Every. Damn. Time.)

But nowadays we are faced with a strange, unprecedented choice: to accept or avoid challenge. Discomfort, too, has become optional. We can side-step and detour. We can opt out with the swipe of a screen.

And if you’re a kid today, you can likely get your parent to fight whatever pesky battles you need fought. Because if you’re a parent today, you likely feel a real pressure to do more, be more, provide more.

The result? Parental interference. (Because we just love them so much.)

We pave smooth roads for our kids, knocking down obstacles to prevent hardship. We spin plates to keep them happy, sparing them disappointment or hurt feelings. We wait on them, cater to them, clean up after them. (Confession: I often do the dishes while my kids sit on the couch with their heads in their phones.) If we have anxious or depressed kids, we try not to rock the boat. We save kids the trouble of hunting for answers themselves or solving a problem. Some of us go full blown helicopter.

We're just trying to make it all a bit easier, a touch softer. We do it because it's hard to watch them struggle.

(Acknowledgement: The fact that we can even choose this road is a facet of privilege.)

But micromanaging and overprotection are not love. They are limitation. They tells our kids: you can’t handle this, but I can.

Of course we can, we're adults.

When parents rescue or intervene, kids don’t learn the discomfort of challenge and the glory of triumphing over it. They become more worried about pleasing their worried parents than engaging in the necessary try/fail/try/succeed cycle of learning and growing.

Kids deserve the opportunity to struggle. Childhood is only becoming more monitored, more anaylzed, more competitive. Parents, in return, are judged by how their children are performing. No wonder we get overinvested and slightly co-dependent; our job performance is on the line.

Here's the thing: under all this pressure, we may have forgotten the actual goal of parenting.

Children get their safety and security from their parents; it’s a scaffolding that holds them steady as they develop. But that external stability is borrowed, on loan until they learn to create their own. And that is, literally, the goal of growing up – a gradual loosening of the essential and dependent parent-child bond in favor of the deep self-bond of adulthood.

Our job as parents is to build a safe container for our kids so that they can outgrow it and strike off on their own.

Separation is built into the design.

It’s a natural, torturous process, one that requires two things: for children to grow their own strength and stability through challenge and for parents to let go.

When we "save" our kids from struggle, we are "saving" them from developing their own agency, power and competency. Because resiliency is a muscle built by use. Challenges teach us how to rise and, more crucially, how to fail. If kids don’t learn this when they are young, with age-appropriate challenges, they will be forced to learn it later, out in the world where the stakes are much higher.

When we buffer kids from the natural obstacles or consequences of life, we groom them to become fragile adults who are dependent on the world treating them a certain way so they can be okay.

And that is a hard, hard road.

There is a Buddhist story about a moth that goes something like this: a human watches a moth struggling to emerge from its cocoon and tries to cut the cocoon to free the creature. A monk comes along and says, “The moth needs to do this on its own. Pushing itself from the cocoon is how it develops the strength to fly. If you free it, you will kill it.”

So how do we support without taking over? How do we stand by and watch them get it wrong when we could help them get it right? Where do we honor kids' needs and where do we ask them to rise to a situation? When does opting out support a kid and when does it limit them?

I wish I knew. Many days I’m all, “Give me the damn knife. I don’t care if my moth can’t fly. I just can’t watch this anymore.”

But the truth is I wouldn’t trade the challenges of my life. I like who they have made me. I admire my own, hard-won resiliency. I like knowing I can handle myself. It makes me less afraid and more daring.

Still, letting go is hard. My oldest leaves for college in a week. (Check on me, k?)

But things have a way of working themselves out. Thirty something years after my hairstyle debacle, guess what happens when I swim in the ocean? I get Bon Jovi hair.